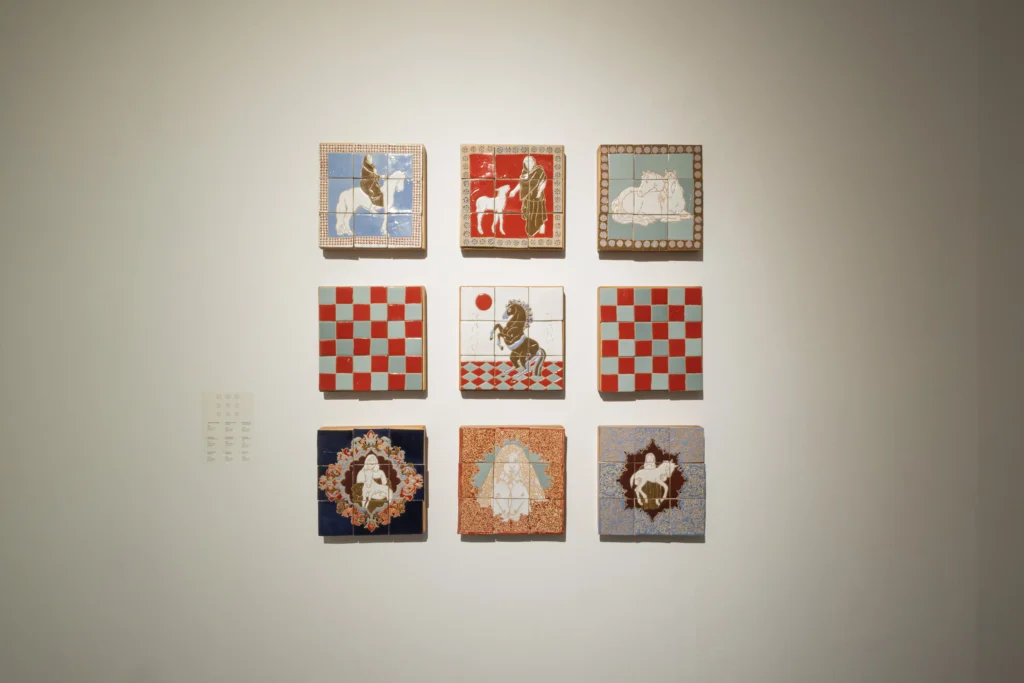

These bodies have appeared before. These bodies have never been neutral. Zuraisa’s practice has persistently returned to the body. Earlier exhibitions such as Setempat (2023) and Bon Voyage (2024) foregrounded corporeality as a condition shaped by pressure and endurance. What marks a decisive shift in her recent work is the reconfiguration of whose bodies are allowed to carry meaning. In The Taurus and Me (2024), a bull enters the picture. In Traces of Eve’s Good Deeds (2025), snakes and tigers follow. In her latest solo presentation, Sweat and Bitter, non-human figures appear once again. This time, it is a horse—more precisely, a mare. The specificity matters.

One work in Sweat and Bitter is especially difficult to overlook, largely because of its scale. Measuring 150×300 cm, The Working Mare (2025) depicts a kneeling mare resting her lowered head, pressed tenderly against the shoulder of a naked woman seated on the ground before her—a self-portrait of the artist. The dark background suggests a moment in time. An orange glow emerges from a circular form—sun or moon, dusk or dawn—refusing clarity. When it comes to work, both readings hold. This ambiguity mirrors contemporary labor itself: without a clear beginning or end. Nine to five, five to nine, it barely matters anymore. Through The Working Mare, work begins to surface as a leitmotif in Sweat and Bitter.

And yet, it would be too quick to settle on the horse and work as mere motifs. Despite the title, The Working Mare does not depict work in action. Instead, it stages a paradox: two figures who could be positioned as laboring bodies—a woman and a horse—are shown not working. What is depicted instead is potentiality: the capacity to work, and the equally important capacity not to. A closer look suggests exhaustion, perhaps even unlivable working conditions—most visibly in the mare’s gaunt body. The woman’s nakedness signals exposure and vulnerability, recalling how feminized labor is expected to remain available and unprotected. And yet, the absence of a bridle, the nakedness of the female worker, and the mirrored, grounded posture of both figures continue to signal a condition of rest or even refusal.

This paradox invites us to look deeper into the world of Sweat and Bitter, urging a brief shift away from labor relations toward what sustains them: relations. In The Working Mare (2025), the relation unfolds between the naked figure and the horse. If we momentarily turn to Jason Hribal’s assertion, drawn from his study of domesticated animals, that “animals are part of the working class,” the bond between the two figures gains weight. There is a sense of camaraderie, grounded in shared labor.

This relation also rests on a much longer history. Consider, for instance, the use of horses in equine therapy, which enables emotional mirroring and the reorganization of affect through relational encounter. In this sense, the intimacy suggested in The Working Mare points to a form of affective and reproductive labor quietly at work.

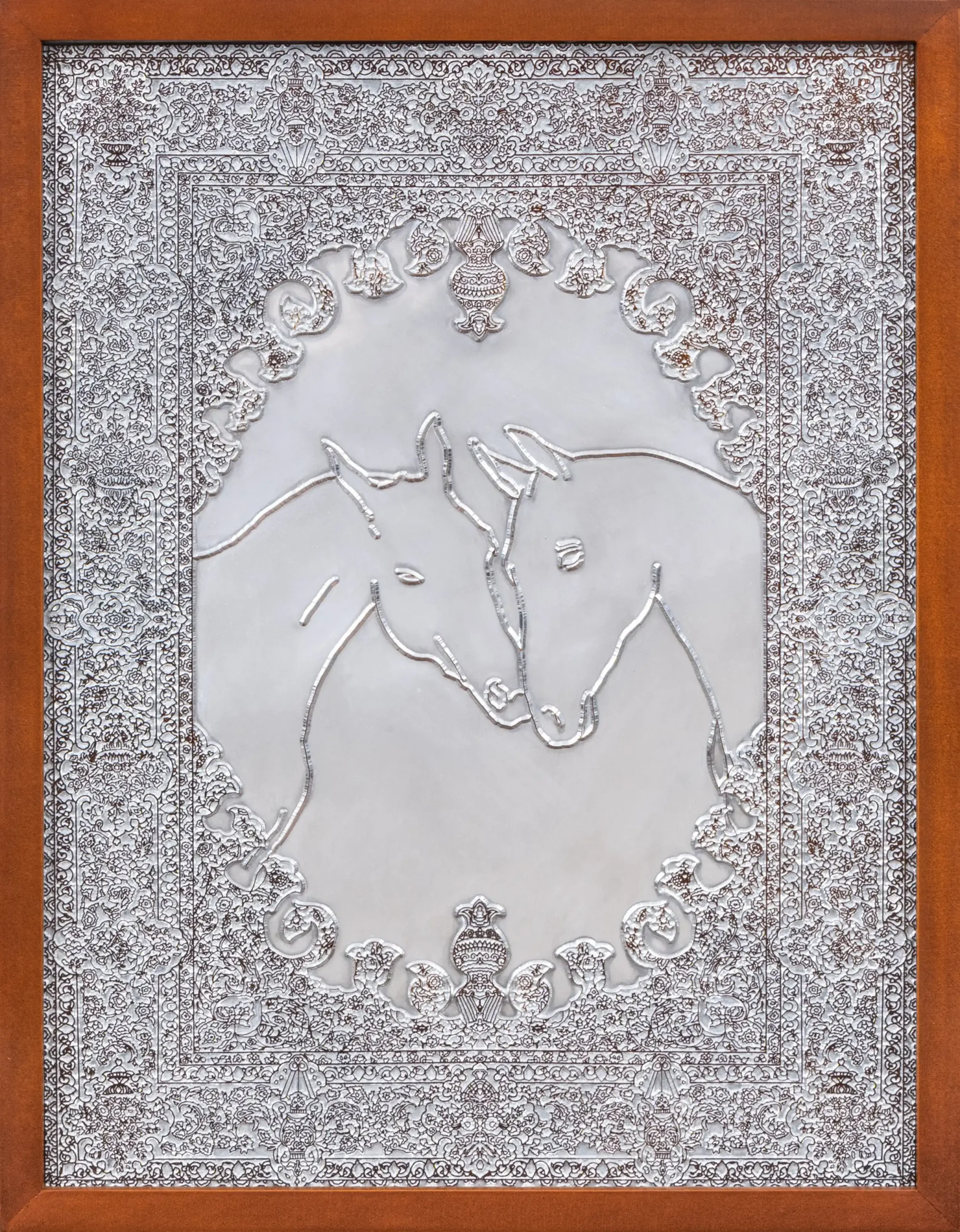

This leads to another important concern in Sweat and Bitter: reproductive labor. Two metal relief works, A Solstice of Rest (2025) and Kinship in the Burden (2025), give form to this concern. In the context of the exhibition, Zuraisa’s metal reliefs recall Ha Bik Chuen’s “motherboards” in Reframing Strangeness (2025): they are artworks, but also tools of reproduction. These reliefs can be used to produce debossed works, which are usually the ones shown. Here, the logic is reversed. The tools themselves are put on display. What is usually unseen—the tool itself, along with the imagined gesture of reproduction—is brought to the fore. Reproductive labor is thus placed on equal footing, not auxiliary to creation, but foundational to it.

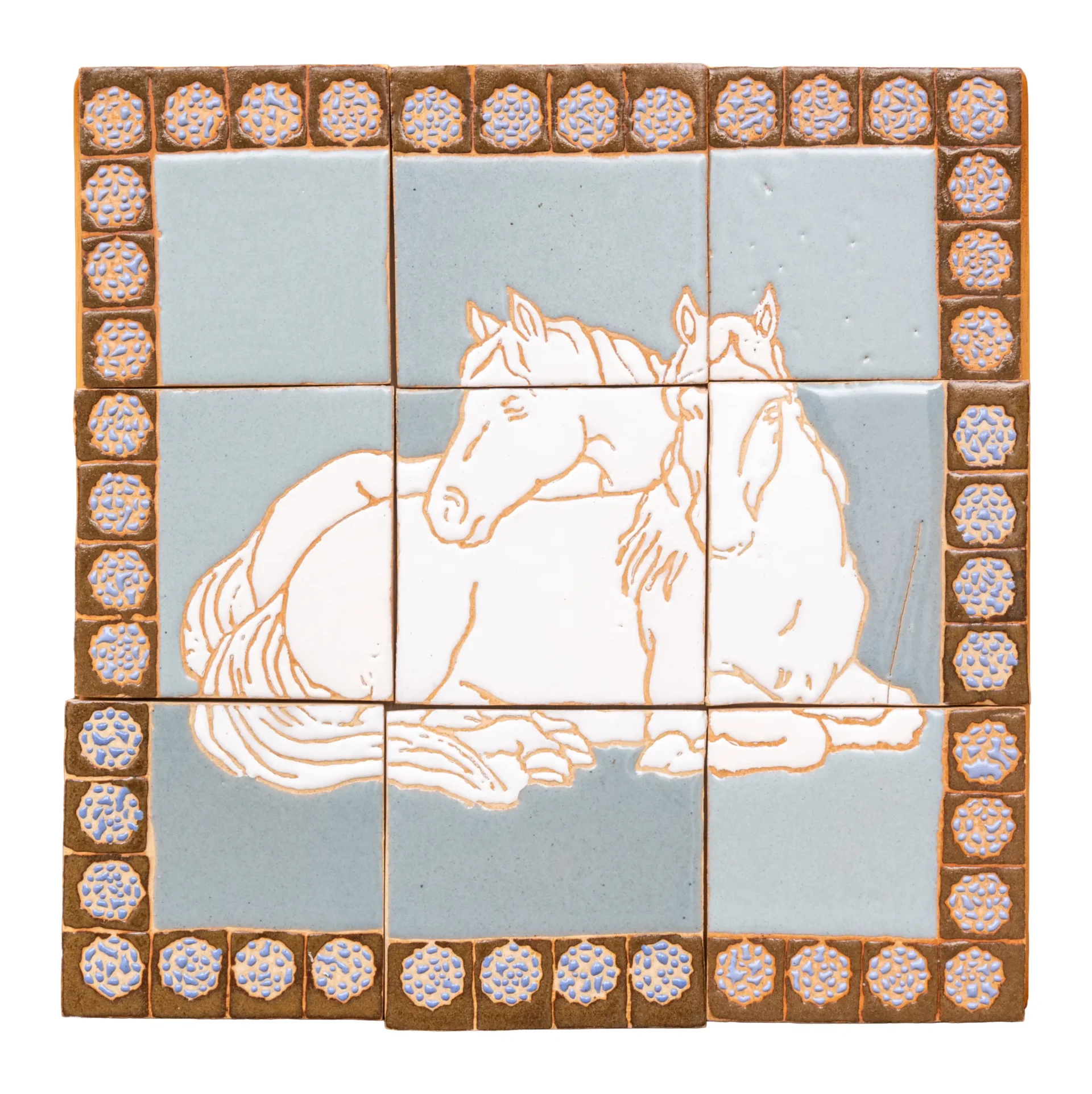

The insistence on making the unseen visible recurs across the exhibition. With the exception of The Breath of Unburdening (2025) and The Working Mare (2025), the horses in Sweat and Bitter appear pale, desaturated, and almost spectral. They are present and absent at once, registering a condition akin to learned helplessness—at play—to witness, to endure, and yet to remain unable to intervene. The silent witness in The Quiet Testament (2025), the understated birth in The Unseen Labor (2025), the overlooked presence in An Ode to the Unsung (2025), and the restrained stillness of Two Souls on a Quiet Ground (2025) all trace the same reality: labor that sustains life is rendered quiet and disposable.

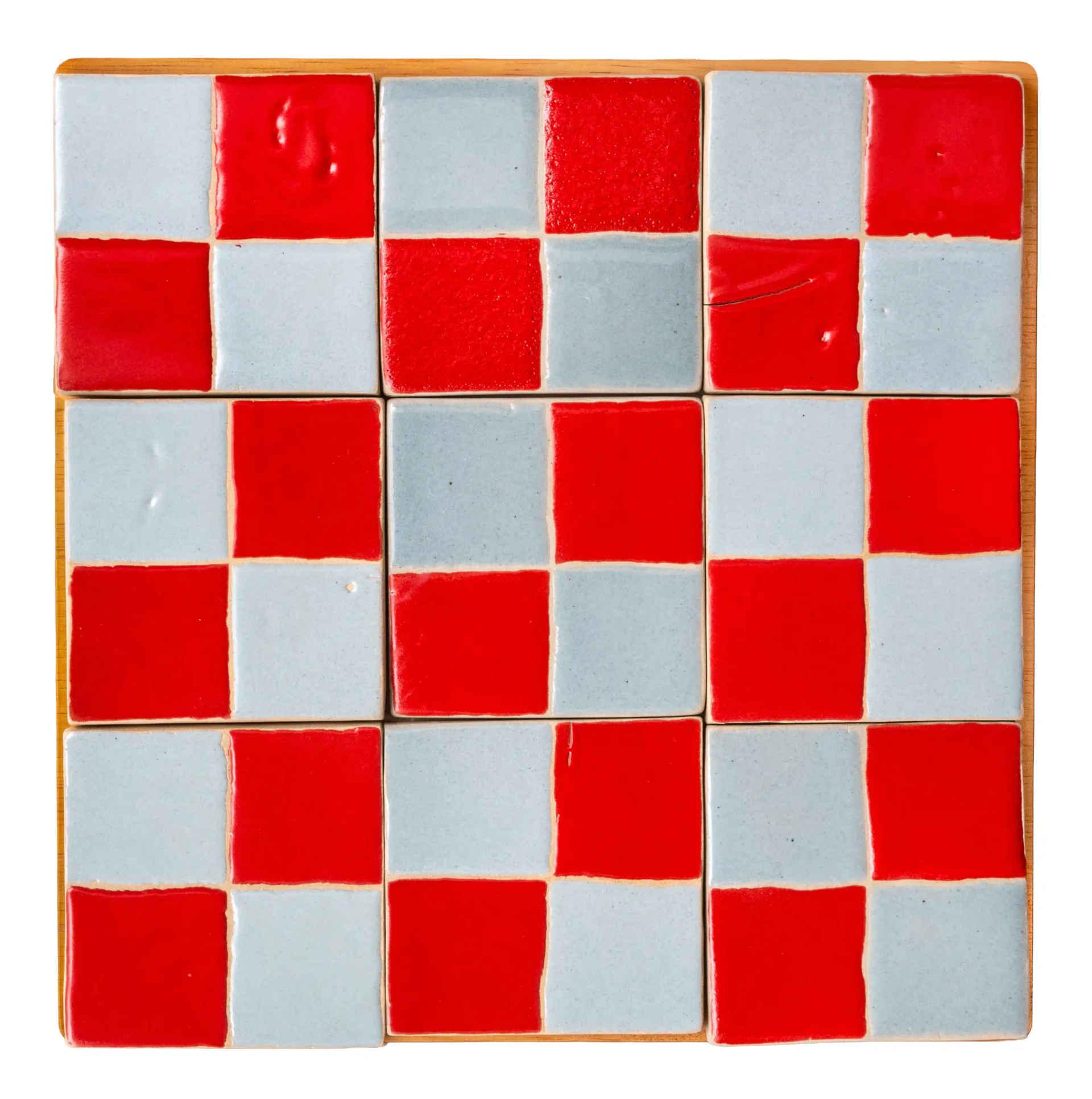

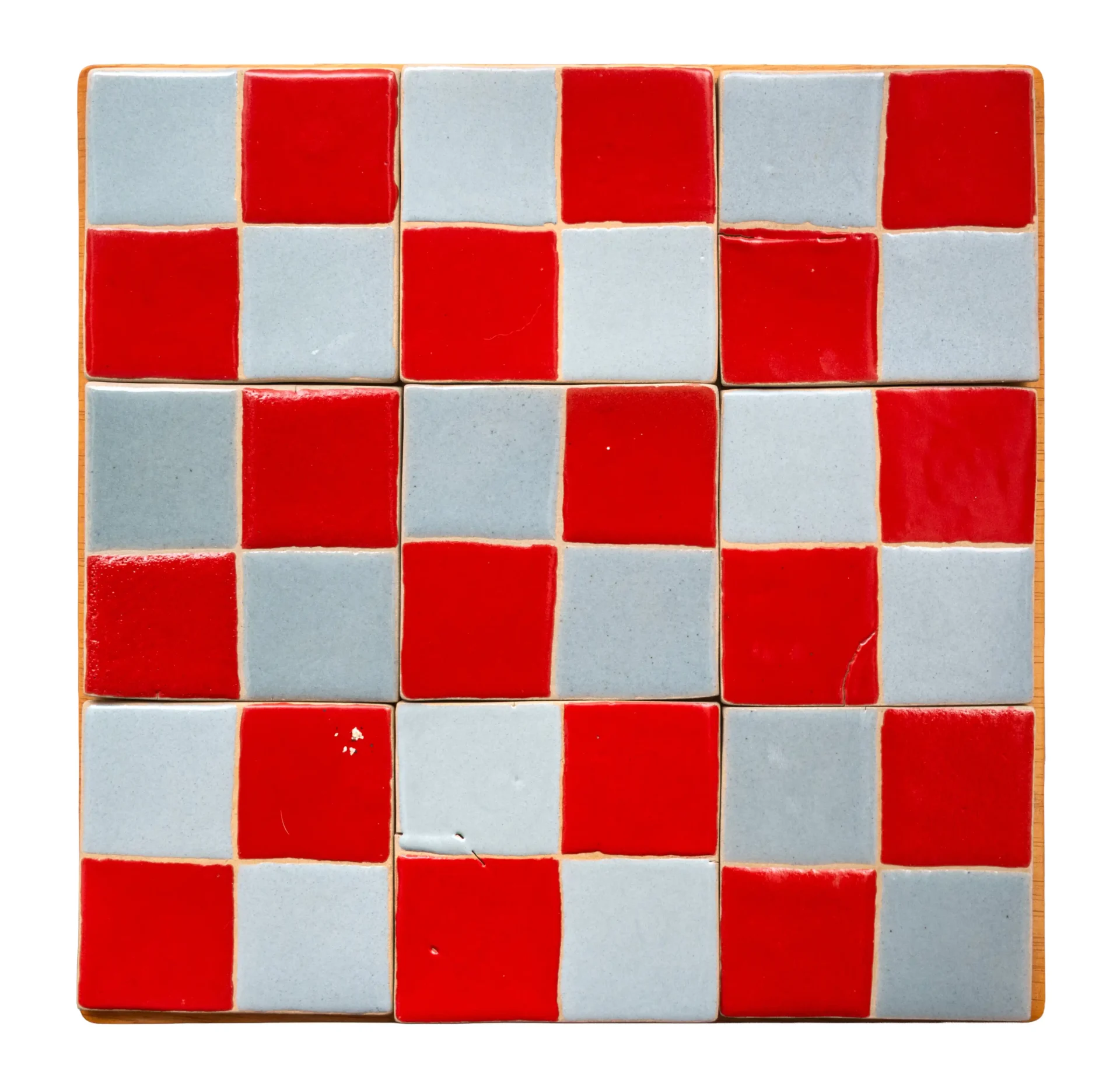

The problem of labor perhaps sharpens in Horseless Chessboard 1.0 (2025) and Horseless Chessboard 2.0 (2025). These works, which move away from figurative representation, nonetheless carry a comparable emotional weight. Constructed from ceramic tiles arranged into 2×2 squares, the chessboard becomes a model of exclusion. The works operate on several levels. Imagine yourself as a horse on a chessboard. In the game of chess, you are called a knight. Despite its supposed neutrality, the term carries masculine connotations, as if to suggest that those who are not male risk being erased from the record. If the board is read as a workplace, Zuraisa’s allusion to patriarchal labor structures—those that continue to sideline women and non-binary workers—becomes difficult to ignore.

The metaphor sharpens further when the logic of the knight’s movement is considered. In the game of chess, a horse or a knight moves in an L-shape. On a board composed of 2×2 squares, such movement becomes impossible. The horse cannot move without rupture. Every attempt to move is met with constraint. This is not an aesthetic accident. It mirrors the experience of navigating systems designed without you in mind—systems that demand participation while quietly denying mobility.

What shifts most decisively in Sweat and Bitter is not simply Zuraisa’s thematic interest, but her method of staging the body. The body is no longer exclusively human, nor is it singular. Notably, rather than foregrounding the ceramic tiles that have characterized her recent works, she returns to canvas. This return is telling, as The Working Mare carries perhaps the most immediate emotional weight in the exhibition, particularly in its facial expressions—heavy, exposed, and unresolved. The return to canvas coincides with a return to affect, a heaviness that feels newly foregrounded. Though subtle, this circular movement in materials offers a clue to the larger trajectory of her practice: that material choices are inseparable from the affective economies they enable.

At the same time, this return signals a reorientation in how the body functions within Zuraisa’s practice. In earlier works such as Chewy Study (2023), the body appeared as a site of abstract possibility—one example being “the possibility to be pinched.” In Sweat and Bitter, the body becomes a site of function. It carries labor, gender, and social demand. The body is increasingly positioned as an instrument within fables of labor. Within this framework, the body is heavy with connotations. It no longer appears primarily as a speculative space for freedom, but as a bearer of connotation, burdened by expectation and use-value. Autonomy over one’s body, when it appears, does so only in potential form—continually deferred under capitalist and patriarchal conditions—as desire, as hesitation, as the fragile possibility of refusal.

Seen closely, throughout Sweat and Bitter, horses often appear against empty spaces, as if to suggest that work continues to loom, even when no one is visibly working. Only in The Breath of Unburdening (2025) does the horse seem to slip free from labor’s grip, while The Working Mare (2025) holds its refusal in stillness. As the year edges toward the Year of the Fire Horse in the Chinese calendar, Sweat and Bitter closes not with an answer but with a reflective question: Is it possible to step away from work through our own agency and reclaim the freedom to rest and to care for one another? Or are we still haunted by the same old image, one that praises endurance, binding the horse to the old saying: to work like a horse?

STEM Projects

Sweat and Bitter

A Solo Presentation by Zuraisa

6 December 2025 – 18 January 2026

Tirtodipuran Link Building A

Jl. Tirtodipuran No. 50

Yogyakarta, Indonesia 55143