When I arrived at the Jogja National Museum (JNM), the scene before me looked something like this: the maroon wall with large letters “ARTJOG” in the middle, tall dry trees towering above, a long queue of visitors in front of the ticket booth, and groups taking turns posing for photos under the letters. This act of photography has resembled a “ritual” for visitors before entering the ARTJOG exhibition hall, as if someone’s presence is only considered “valid” after taking a picture in front of the iconic façade.

From witnessing these gestures alone, one could already sense that ARTJOG has never been just an exhibition. Before going further, I will first outline several points that become the focus of this writing. The story above I took from ethnographic research that I carried out at ARTJOG. Throughout the series of writings, I will talk about the exhibition, the spaces that are presented, its visitors, the photographic practices inside, and how the theme of ‘amalan (practice of good deeds)’ interprets fine arts today. Over the years, it has grown into an arena where art, space, and the public continually redefine one another. In this eighteenth iteration, I wanted to trace how ARTJOG has matured as a living practice, a journey of becoming that reflects its own journey and the changing ecology of Indonesian contemporary art.

The Shape of a Trilogy

The 2025 edition of ARTJOG took place from 20 June to 31 August, involving 47 artists by invitation and open call, as well as 44 kid artists through its education platform. This year also marked the conclusion of the trilogy of themes under the title Motif, beginning in 2023 with Motif: Lamaran (Proposal), continued in 2024 with Motif: Ramalan (Prophecy), and concluded in 2025 with Motif: Amalan (Practice of Good Deeds). This final theme invites a reading of artistic practice within the tension between the autonomous world of art and the heteronomy of daily life, between one norm and many norms.

In 2023, ARTJOG proposed itself to the arts it wanted to nurture; in 2024, it looked ahead, imagining the future of artistic practice; and in 2025, it grounded itself on acts of practice that connect art to life. In its everyday language, “amalan” refers to deeds or actions, often in the context of worship and kindness. However, at ARTJOG, this term is read more broadly, covering the actions of organisers, the works of artists, and the experiences of visitors. In other words, “amalan” is not merely a thematic concept, but a shared practice that lives in the space of fine arts, both inside the gallery and outside, through visitors’ cameras, conversations, and memories.

Anusapati and the Surprise of the Façade

I will begin this writing from the façade, where the narrative of the exhibition begins. This year, ARTJOG entrusted Anusapati (b. 1957) to work on the façade. He presented towering dry trees with hanging roots, a trolley and railway tracks, as well as wooden totems placed in a seemingly random manner. The installation, Secret of Eden, brought the uncanny atmosphere of the ‘earth’s core’, like a dark space lit by spotlights so that the shadows split the wall and floor. This commissioned work pointed to the ecological crisis while also opening a space for reflection on human–nature relations.

From outside, visitors saw dead trees towering; once inside, visitors found themselves surrounded by hanging roots at eye level. Then, on the second floor (mezzanine), they once again encountered the dry trees under night spotlights that cast shadows onto the walls of the exhibition building. This three-layered encounter created a participatory choreography, so that the audience not only looked but were “inserted” into the body of the earth and even moved along with the work.

For me, this was where the word amalan first manifested. ARTJOG seems to “practise” the artwork not only through the piece, but also through the ritual of experience. Three “photographic” events are presented in sequence. Firstly, from the front, visitors are faced with tall dry trees that arouse curiosity as well as awe. Secondly, in the first room they enter the ‘earth’s core’, directly confronting the hanging roots at eye level. And finally, from the mezzanine on the second floor, they again see the row of dry trees, now unevenly arranged yet parallel to their own gaze.

Dark–Light Rhythm

Entering the exhibition hall inside, one immediately senses how sace functions as an active agent that shapes experience. The white corridor with hand sculptures by Budi Santosa, for example, becomes a simple ‘gateway’. The symbol of the hand can be read as a sign of victimhood, surrender, or prayer, so this corridor works as a pause after the dark and monumental façade. This transition is important because the visitors’ bodies are given time to adjust before entering the three main floors.

After passing through the corridor, visitors directly enter a wide dim room. Here the first work to be seen is the painting of Herru Yoga. He raises the theme of collective trauma due to war, death, and deep grief, but not with gloomy colours. On the contrary, the dominance of white actually creates a paradox, as if the banality of the tragedy of war could be told without darkness. The dim lighting strengthens the impression of intimacy, so that threats in the form of fear, cruelty, and even a “pointed weapon” seem to be present in the room. Facing this work, S. Urubingwaru installs paintings that slice through the room like abrupt partitions.

Meanwhile, on the other side, the work of Syagini Ratna Wulan offers a different contemplation. She raises the relation between image and eye, examining the flood of images in digital culture and presenting “hyperreality” through the symbol of eye-vision. The paintings are arranged in layers to simulate the overstimulation of social media.

As I moved through this room, I realised that the play of dark and light was itself an amalan, a practice of curating emotion through rhythm. Dark and light, wide and narrow, calm and noisy, all these create a dramaturgical flow that guides how someone lives through the works. And, as I noticed, these rhythms also shaped how visitors used their cameras. Dark spaces with dramatic lighting encourage them to take artistic photos, while bright and spacious rooms more often become the backdrop for selfies or group portraits.

Collective, Participatory, and Social Practices

Darkness and light alternating throughout the exhibition space create pauses as well as moments of contemplation amidst the density of works. From there the journey continues to Murakabi’s installation, presented in a darkened setting and highlighting trasah watu, a rural technology practice for hardening roads. This practice carries strong ecological meaning, as it allows water to be absorbed properly while also reminding us of construction methods from the past. Murakabi emphasizes the aesthetics of visual art while also opening a space to learn together about the wider relationships between humans, nature, and space.

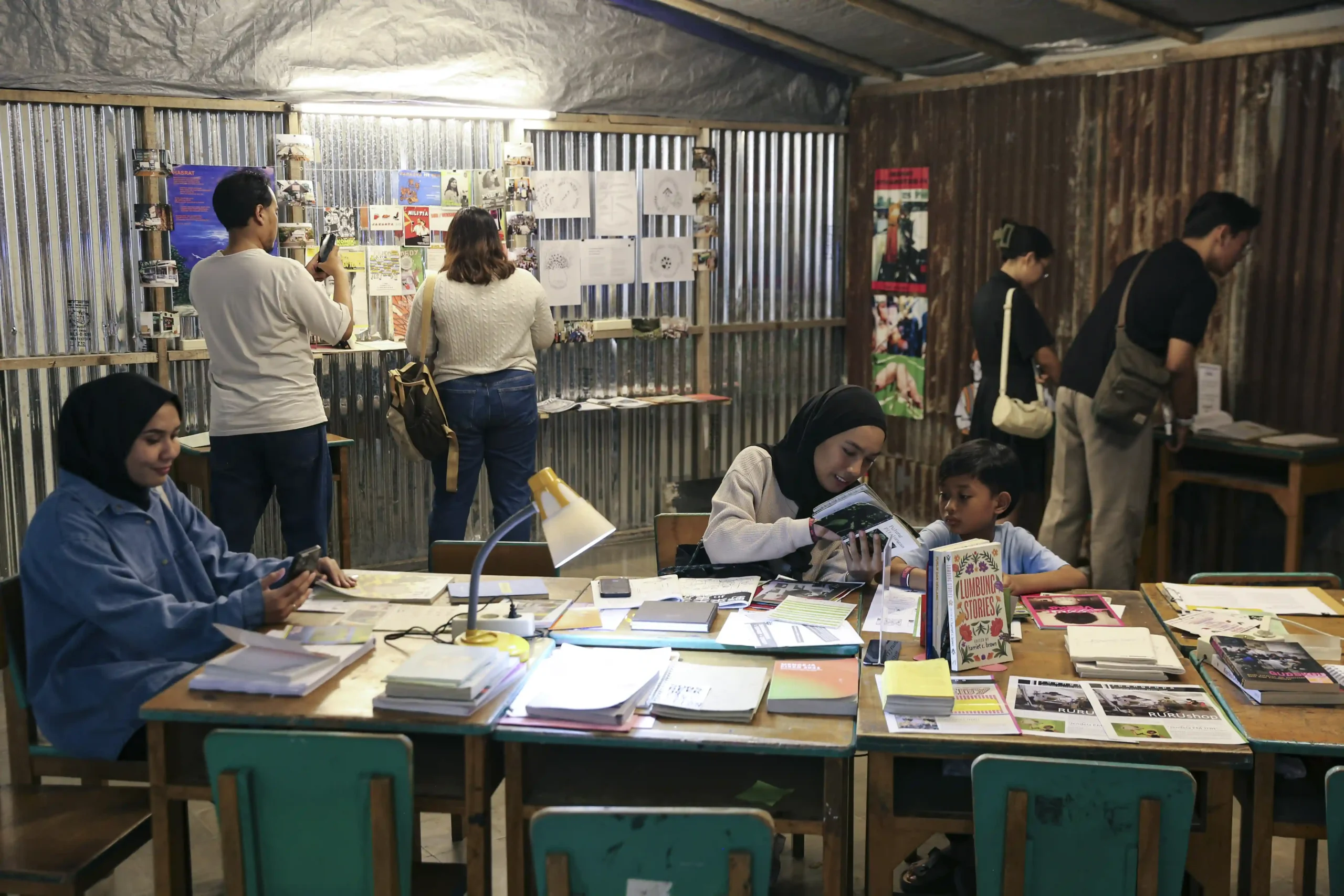

The connection between art and education then becomes apparent in the collective work of ruangrupa (ruru), which showcases their artistic practice over the past decade. Through the Institut ruangrupa (ruangrupa Institute) (Ir), they reflect on new and increasingly complex challenges in art education. For this exhibition, Ruru presented Perguruan Tamanruru, referring to Ki Hajar Dewantara’s founding of Taman Siswa in 1922. The presentation takes the form of book archives resembling a library, desks and chairs arranged like a classroom, and instructors taking turns giving lessons. Over the course of nearly two months, eleven selected participants took part as “students,” turning this classroom into a living practice of learning.

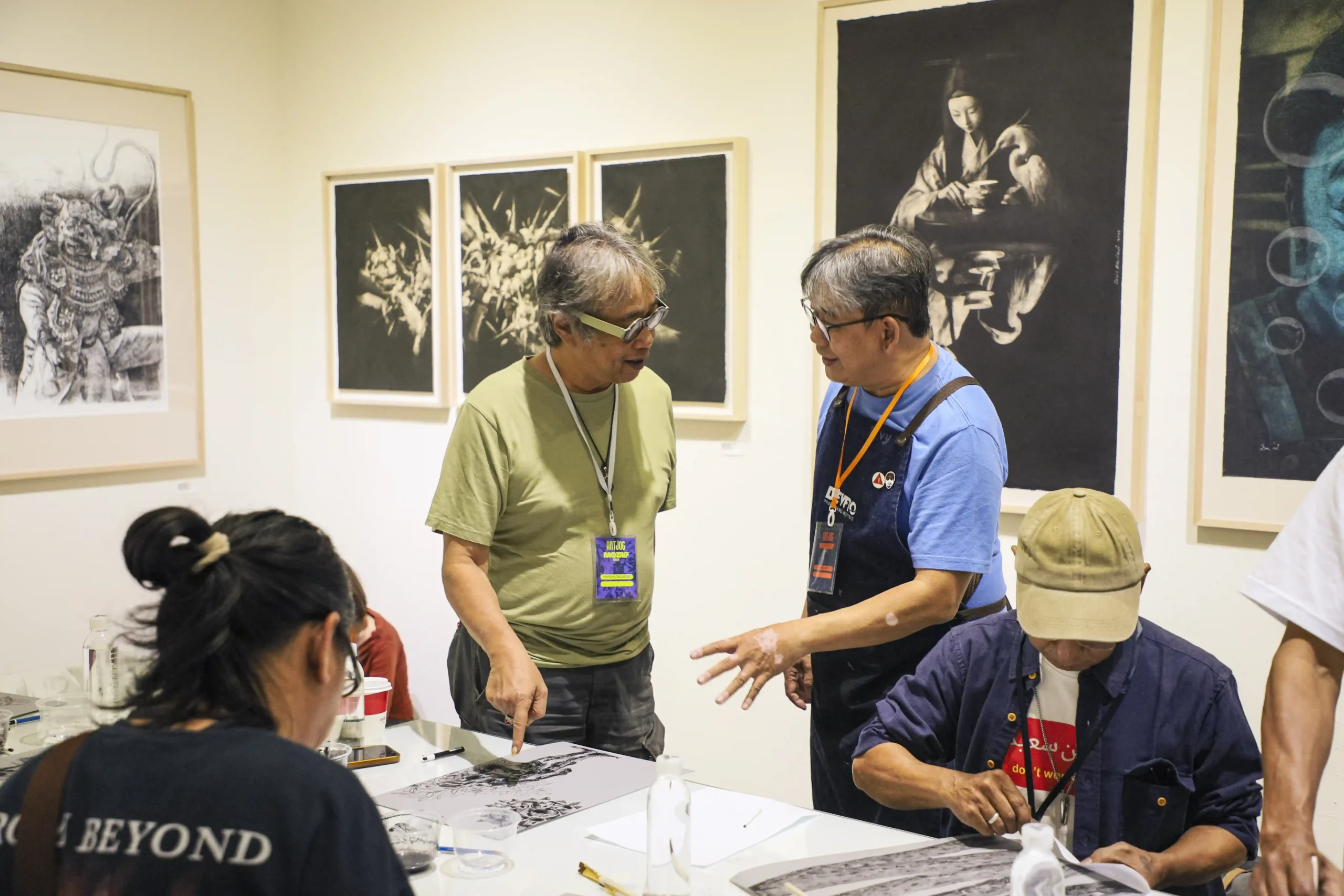

From here, it becomes even clearer how groups of artists bring forth collective practice. Alongside Murakabi and Ruru, several other collectives such as Devto Printmaking and Klinik Rupa Dokter Rudolfo also occupied the exhibition space with their works. This form of “grouping” is especially relevant to the theme Motif: Amalan, which refers to practices that extend beyond the individual into collective work. This was further emphasised by RE Hartanto’s action through Klinik Dokter Rudolfo, which invited the public via Instagram to participate in a collaborative workshop painting 350 canvases. With a fee of Rp100.000,-, anyone could take part, and their works were eventually exhibited at ARTJOG. This act demonstrates that practice is not merely a symbolic ritual, but a real act of sharing space.

Thus, the first floor becomes a space that can be read most clearly in relation to the theme Motif: Amalan. Collectives, everyday narratives, and spaces of shared learning are connected through fluid forms of participation. The spatial partitions also guide visitors to move smoothly from one work to another. From this experience, I felt that the idea of amalan was most vividly expressed through collaborative work and the involvement of many parties.

Intimacy, Isolation, and the Banality of Spaces

The transition to the second floor is marked by the work of Raden Kukuh Hermadi, installed along the staircase. His piece, Selepas Tegalan, brings a local narrative from Gunung Kidul, his birthplace. Using burlap stretched across both sides of the stairs, he presents a landscape of Gunung Kidul after massive deforestation. The texture of the burlap itself recalls wartime hardship, so this installation conveys both fragility and toughness like a trace of memory forced to endure amid the passage of visitors moving up and down.

Upon entering the second floor, the atmosphere changes drastically. A long corridor with tight partitions on both sides of the room makes the experience feel exhausting. The JNM building, once the classrooms of ASRI (Academy of Fine Arts Indonesia) before its conversion into an exhibition space, now presents smaller sectioned rooms as if prepared for each artist’s solo show. For me, this “intimacy” instead brings a sense of banality, since the works on this floor mostly stand alone without blending into one another.

Take Beawiharta, for example. This senior photojournalist exhibited four diptych photographs pairing past events with the present. His well-known work, Indiana Jones Bridge, shows school children crossing a nearly-collapsed bridge in Ciherang River, Lebak, West Java, in 2012. The photo once circulated widely in international media and even prompted donations to repair the bridge. Beside it, he displayed a portrait of a mother of two. The same person, Aan Rosidah, who was a junior high school student he had photographed thirteen years earlier. These two photographs were printed at a monumental scale of 250 x 600 cm.

Bea’s work did not stop there. On another wall, he presented a monumental diptych on the 2004 Aceh tsunami refugees. One image shows a group of people walking for six hours through damaged roads in search of food, while twenty years later, he photographed Sabariah and her son Fastabiqul again, this time in a green hilly field near their home. He complemented this series with detailed captions for each photograph. To me, Bea’s long-term project represents a form of practice (amalan) toward photography that he has devoted himself to for decades, as if his exhibition space became a solo show filled with dedication.

After Confinement

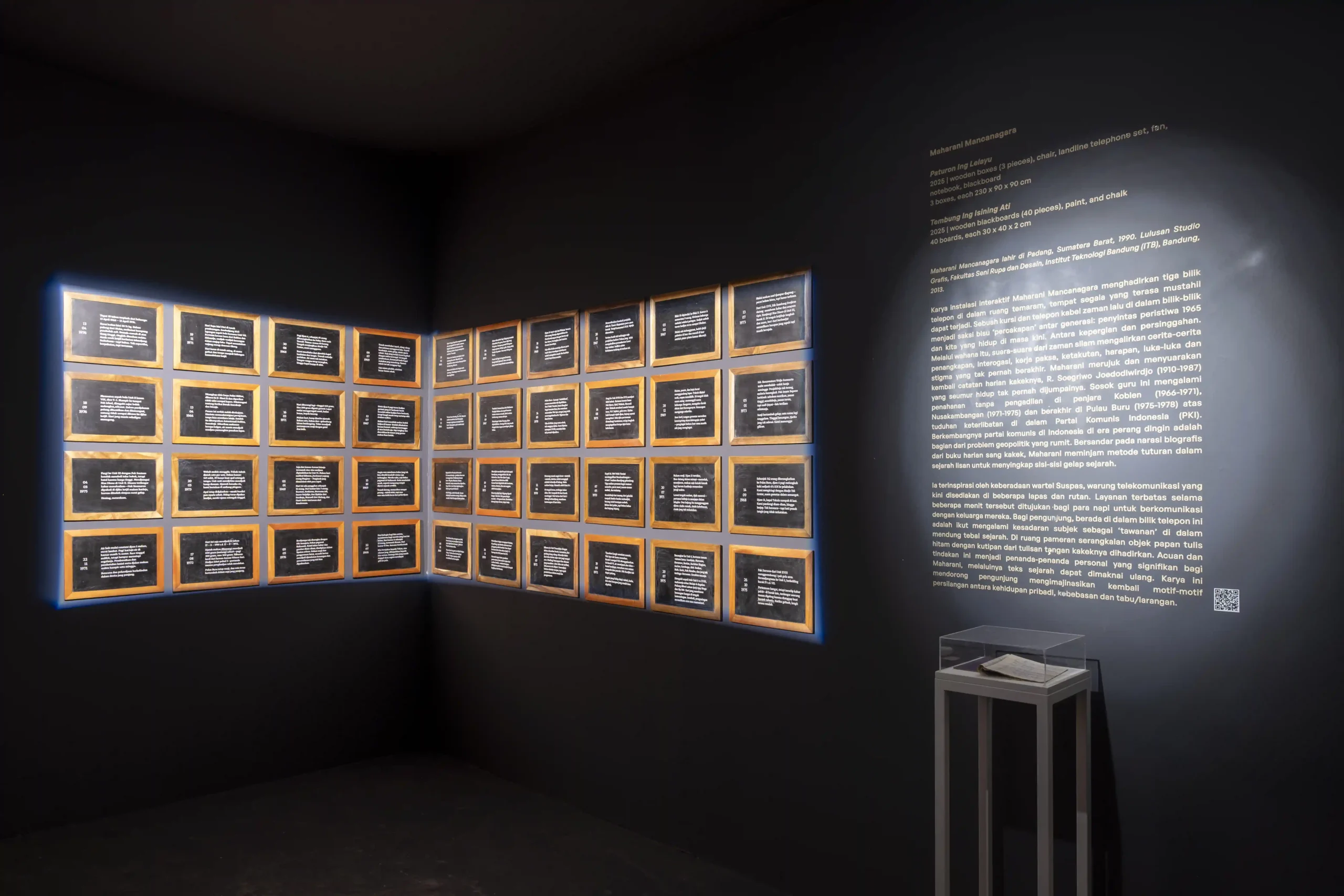

After the narrowness of the second floor, the third level offered a sense of release. The space was open and bright, allowing visitors to breathe again. Among the fourteen artists here, Maharani Mancanegara’s Paturon Ing Lelayu; Lembung Ing Isining Ati (2025) was an interactive installation in the form of three telephone booths placed in a dimly lit room, each containing a corded telephone and a chair. The starting point of her work was inspired by the existence of public phone stalls provided in several prisons and detention centers. Visitors were invited to become subjects within the work, imagining themselves as prisoners communicating with their families. Inside the booths, they could listen through the telephone to a conversation in which her grandfather described his condition to his grandchild. In this work, she referred back to the diary of her grandfather, whom she never met. He had been accused of involvement in the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Maharani transformed his diary into a spoken narrative as a way of retelling a darker side of history. In the room, she also presented a number of blackboards inscribed with excerpts from his writings.

Two Visual Arts

In the process of writing this essay, various reviews and discussions about texts concerning ARTJOG as well as visual arts in general took part in shaping this writing. I slowly read various articles and books along the way as references in this writing process. I recalled an essay by Sanento Yuliman, which was discussed in one of my university classes, which was his article from the Jakarta Arts Council Symposium in 1984, titled “Two Visual Arts”. In his writing, he discussed the polarity in visual art between high art and low art.

For Sanento, high art developed only among the upper-middle class, depending on Western aesthetics, and was oriented towards the market and modern lifestyle. Meanwhile, low art grew among the lower-class society, rooted in tradition and simplicity. In his essay, Sanento criticised the existence of a single, homogeneous view of the history of visual art and rejected the domination of painting and sculpture as the only forms of visual art. He criticised the imbalance between high art (paintings and sculptures integrated within the global and exclusive market system) and low art (folk paintings, pedicabs, folk crafts produced for customary needs and local markets). This imbalance, according to him, created a sense of inferiority and superiority.

In his writing, he also criticised the educated class who tended to consider low art as a product that lacks aesthetic value. Sanento encouraged a more inclusive and contextual reading of the development of visual arts, one that is grounded in real situations, not only from the perspective of high art (Western modern art).

ARTJOG and the Space (without) Boundaries

In this long article, I read what happens in the 2025 ARTJOG movement while bringing forward the emphasis written by Sanento Yuliman in his discussion on the two visual arts.I compared two artworks displayed on the first floor that resonate with Sanento Yuliman’s writing on high art and low art: the works presented by Surya Adiwijaya and Veronica Liana.

Surya’s work discusses the tradition of blacksmithing, which is increasingly displaced by the sophistication of modern tools. His work is presented through an installation consisting of hoe blades, hammers, sickles, and artificial embers made from LED lights — a work that mostly uses everyday objects commonly found in a blacksmith’s workshop.

Meanwhile, the work beside it, by Veronica Liana, discusses her new daily activity as a mother. Her work is presented by forming everyday objects such as children’s toys, chairs, eating utensils, cooking tools, flip-flops, and even a laptop.

Both artists address daily activities in their artistic concepts — Surya by highlighting a daily activity that is soon to disappear with time, and Veronica by exploring her new daily routine as a mother. Yet the two differ in the medium of their artistic presentation.

Through these two works, we can see a harmony with what was discussed in Sanento’s essay. For me, this year’s ARTJOG exhibition becomes a manifestation of what Sanento once wrote. A merging of the two visual arts. By releasing such singular interpretations, high art and low art dissolve into one another, without separation. Both works are viewed as equal in the same room: Surya, who brings everyday objects in their original form, and Veronica, who shapes three-dimensional realism using canvas fabric, which is a medium that has long been regarded as the main one in painting, and thus often associated with the high art Sanento discussed.

Eighteen Years of ARTJOG

For me, today’s visual art has returned to the discussion of everyday life. Into something ordinary, without needing manifestos, without the burden of representing an era, where the distinction between high art and low art has dissolved into something no longer plural nor linear.

This year, ARTJOG’s eighteenth edition closes with the main theme Motif: Amalan (Motif: Practice), which I interpret as ARTJOG’s effort to “give” or “make a contribution” to a broader scope of visual art. My reading of this trilogy over the past three years is as follows: in the first year, 2023, ARTJOG proposed itself to the arts it wanted to build towards maturity; in 2024, it predicted what might happen in the future of visual art; and finally, in 2025, ARTJOG surrenders itself to belong to a wider public, to be enjoyed by anyone.

In this eighteen-year journey of ARTJOG, I see it as a stage of maturity. If imagined in human age, eighteen is the age of a teenager who has just finished high school and is focusing on life choices — whether to pursue higher education or to start working. This age marks a turning point for what lies ahead. Likewise, at its eighteenth year, ARTJOG is at a focal point — reflecting on what it wishes to produce in the years to come.

The Following Years

That is what I can outline and explain from the ethnographic observation I carried out at the ARTJOG 2025 exhibition, by discussing the visitors, photographic practices, the artists’ works, and the two kinds of visual art. I hope my writing can serve as a discussion to see visual art in a wider perspective, without boundaries. Lastly, I would like to set out some hopes that I have in mind for the upcoming years of ARTJOG.

Firstly, for the following years, if ARTJOG continues to use the trilogy format, my hope is that the invited curator could be a woman. I am curious about what kind of new perspective might be presented by a female curator in seeing ARTJOG as a wider arena of visual art as it approaches its two-decade journey.

Secondly, would it be possible next year if JNM allows ARTJOG to slightly change its layout (by opening up the divided spaces) on the second floor of the JNM building? Reading this year’s ARTJOG felt rather monotonous, moving from one room to another that only presented “as it is.” I wish to see how this challenge could be addressed by creating a different flow from the previous years.

Thirdly, my last hope in this writing is whether the façade in the coming year, and throughout this trilogy, could be presented by young artists. By seeing how visual art is being discussed by the younger generation, apart from responding to the given theme, perhaps the artists could also reflect on ARTJOG’s own journey. If ARTJOG still relies only on established artists to occupy the facade, I think there are many young artists who have already marked their place in the broader field of visual art.