Saturday, May 24, 2025

An Afterthought: The Romance of Disclosure In(dies) Economy

Contributor: Jasmine Haliza

Let me show you a snippet of the introductory sentences from the exhibition In(dies) Economy, held on March 16 – April 15, 2025, at JNM Bloc, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

In This Economy, when work should be the means to sustain human life, increasingly becomes a source of torment and grows ever more elusive, we have every right to tremble.

We tremble because the concept of “I” no longer exists, replaced only by “Employee X, Worker Y.” We tremble because rest is nothing but a pause and a recharge, just to keep the money machine turning again—

We tremble because half our day is spent on something whose outcome we barely understand.

All this trembling is expressed in an intimate and straightforward voice.

Some might doubt, saying, “What do these kids really know about work, huh?!”

Right, I was doubtful when I entered the conceptual space of Sabloy Station, a design agency under the auspices of Titik Kumpul Forum. The agency’s practice is rooted in using design as both a medium and a basis for creating its works of art.

A challenging and defensive perception emerged as the installations roared into a visual circus, offering various forms of expression of reality from the five artists participating in the exhibition.

In such a way, one of the views in my effort to fathom the casual introduction by Dhias Nauvaly, “In(dies) Economy,” was yet another form of portmanteau phenomenon of contemporary aesthetic strategy.

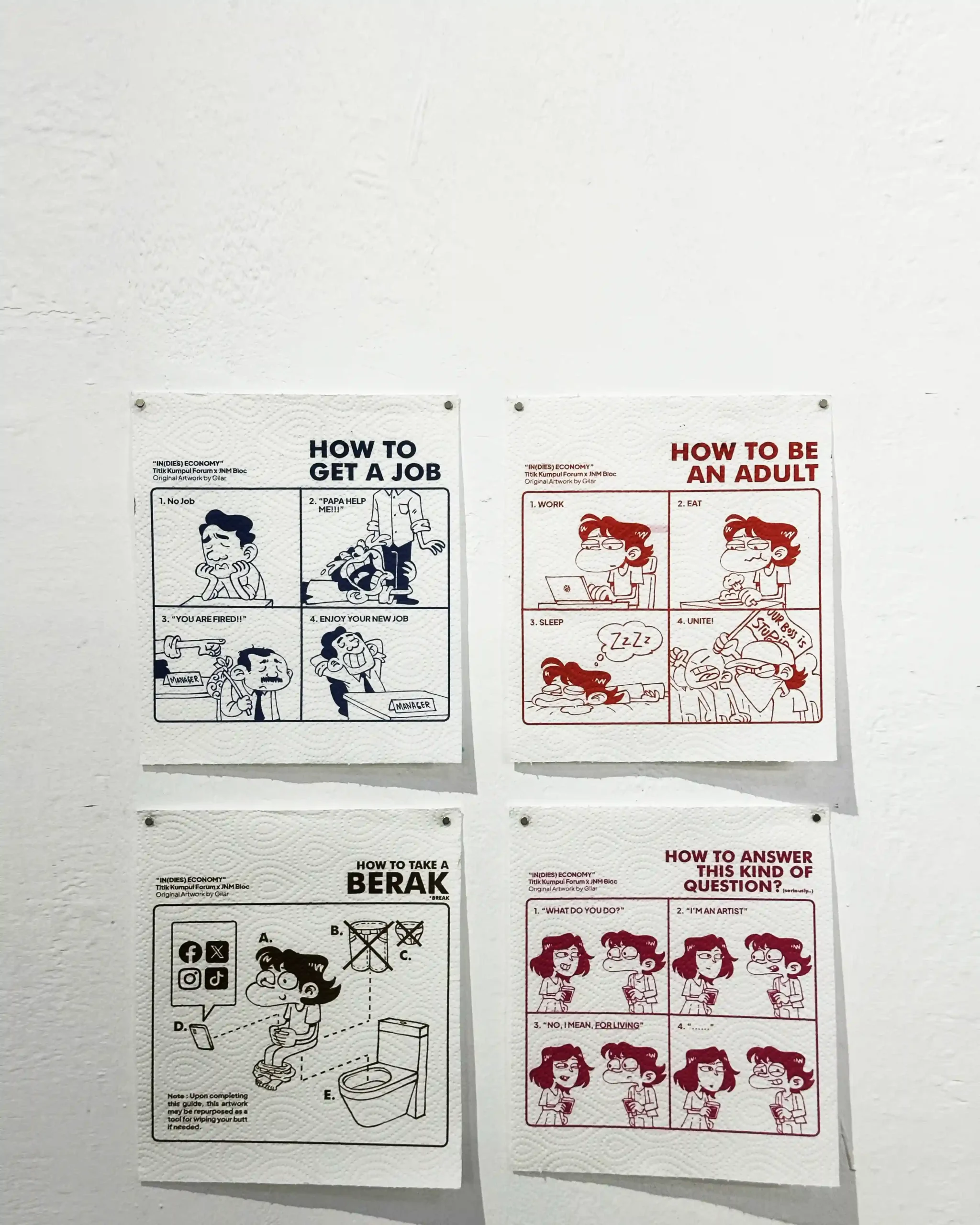

A raid of visual sarcasm; a metal tissue dispenser labeled “Manual Instructions” dispensing comic-style how-to guides; how to get a job, how to be an adult, how to answer interview questions, how to poop. A faux office cubicle populated with satirical cartoons, sketches, and mock “official” documents. Drawings depict anxious, wide-eyed characters, workplace microaggressions, and nihilistic commentary; “No Mercy – No Life – Fucked by Government”. A paper napkin hanging from a bracket with a sign labeled “STUPID EARTHQUAKE DETECTOR”. Revolver with cylinder removed, cigarette butts in an ashtray, scattered newspaper, and handwritten notes. CCTV camera of “the big brother”, up to familiar formats of office signages with subversive text, such as “NO SMOKING! Unless the building is on fire”, showcased the narcotic pessimism of postmodernity.

On the first intellectual trajectory, I accused the entire room of being agents who were ‘straw-targeting’ the world of labor through a heartbreak. As Nauvaly introduced,

“We go to school so we can go to university, and we go to university so we can get a job and once we’re working? WHAT KIND OF WORLD IS THIS?

-It’s this kind of shock that sparked the creation of the exhibition ‘In(dies) Economy’,”

I was pondering how the artists were “just” experiencing a stage of existential dread. A narrow lens, I admit. However, in my defense, it stemmed from a critique, or let’s say, disquiet, of the romanticism of a culture which sees the world as ungrounded and indeterminate where rational discussion and critical enquiry are often undertaken with a lack of gravity, replaces truth and objectivity with irony and ambiguity, coupled with a tendency to drift away from it. In Eagleton’s view, this leads to a loss of seriousness in intellectual engagement and ethical grounding.

The exhibition, which consisted of Ason, Awi Nasution, Gilar, Kay, and Tocka, was another form of Titik Kumpul Forum’s spiritualism in its romanticism towards the ethics of their generation. Inverted world-view building and highly narrated identities became the norm and gained significant tolerance, especially in the context of their curatorial value. In this fashion, as Nauvaly explained, the artists of Sabloy Station took their right to criticize their views and structure of anxiety about their possible future after years in educational institutions, wrapped in humor, nostalgia, and a touch of satire.

The works in this exhibition spoke of fatigue, unclear goals, and the absurdity of life in a capitalist work system. The visual approach was fluid and personal. The artists acknowledged how this generation had grown accustomed to viewing their future bleakly, (almost) expecting dystopian outcomes from technologism and government overreach.

My concern lies more in how we continue to be presented with such ethics from various creative lines, rediscover this kind of curatorial experiment, and be left without a productive way of acting. Looking at how these visual exercises were heading, my defensive perception resolved from my (habitual) engagement with the mood of this romanticized culture, along with apocalyptic hope among these senses of “doomed” or constant crisis.

This particular concern was filled with ambivalence, although in a more nuanced appreciation of the aesthetic strategies that Sabloy Station was pursuing, the vocal points of the installations were progressive when we could generate a familiar kinship between our own experiences of labor spaces with the elements installed.

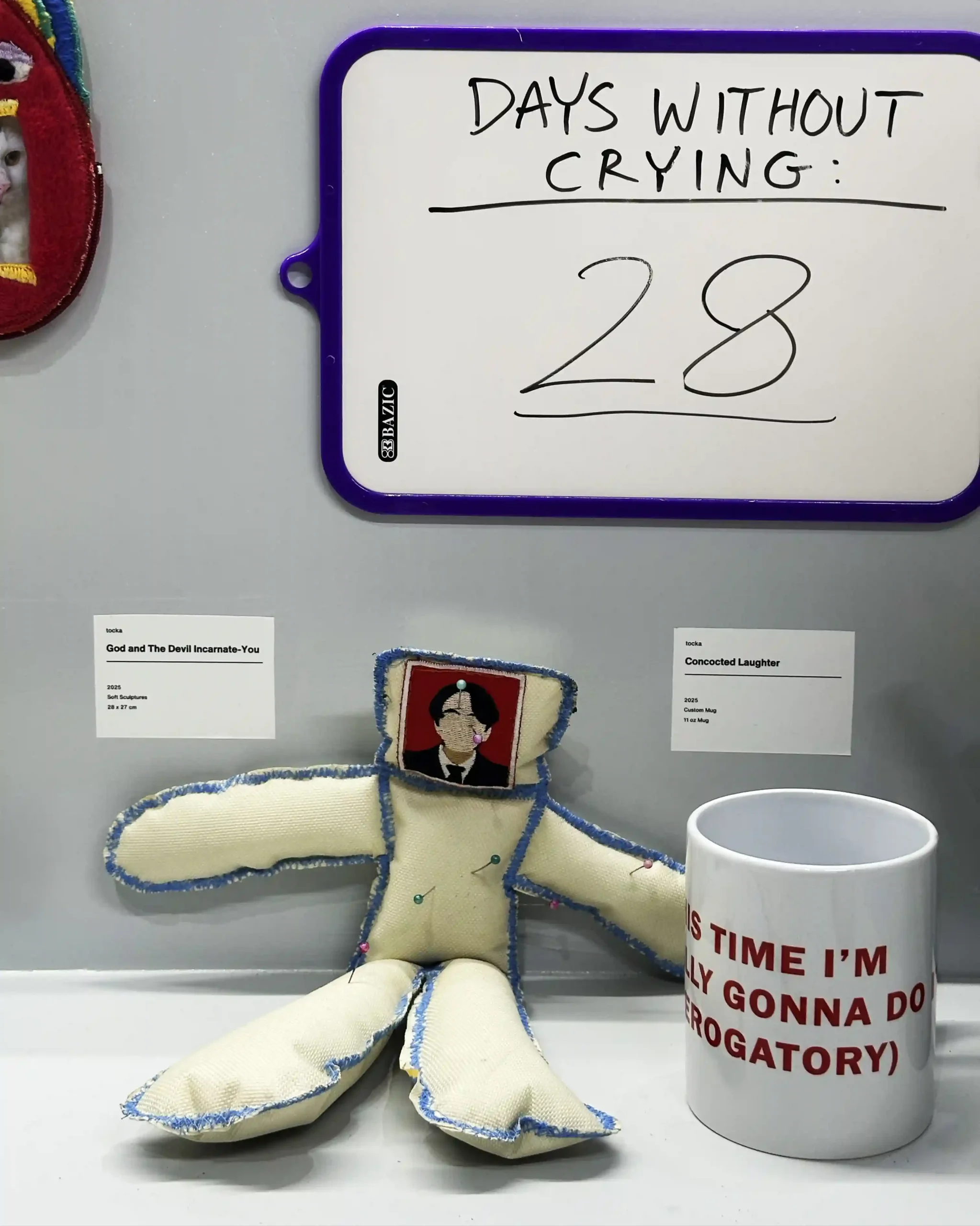

Tocka’s fiber-based soft sculptures (e.g., “A Worker’s Sword, Mortally Double Pressed”) were emotionally evocative, merging domestic handicrafts with symbols of corporate servitude. The medium itself—soft, tactile, handmade—contrasted with the rigidity of office life. There was a deliberate return to childlike creativity and silliness. Compatible with interactive jazz like “I’ve been here for too long, I started seeing things” by Kay, played as both a coping mechanism and a protest.

Kay’s “Pixelated Office Supplies” Series, like “I spilled my pixelated americano” and “Submit on Time”, using screenprints and acrylic mounts, dissected the banality of office life through gamified aesthetics, perhaps inspired by 8-bit games or simulacra like Papers Please. There was an eerie humor in how life was reduced to files, timestamps, and missed deadlines.

“Dekonstruksi Pocong: Karangan Bunga Padi Tumbuh” by Ason’s, a mix of wire, prints, and weapon replicas, explored the ghostly remnants of identity and trauma, tying local mythology with structural critique.

Ason’s desk scene with gun, cigarettes, and newspapers resembled a noir detective’s desk or a journalist’s workspace. The gun and cigarettes evoked a gritty, edgy yet solitary atmosphere. The newspapers, with titles suggesting investigations and ghostly themes like “Pocong”, introduced elements of horror fiction. I suspected that he brought sensationalism to the media and desensitization to violence via the romanticization of noir archetypes.

One of the most significant notions that I encountered was the pillow-like sculptures by Awi Nasution, forms resembling squashed pillows, some with folds or creases that evoked exhaustion, deformation, or even submission. Arranged clinically in cubicle corners, I found a familiar vignette of an experience; they suggested burnout, emotional weight, or the residue of human presence left in monotonous workspaces. They appeared like once-functional objects (pens, cases, mouse pads, glasses, or padded office tools) that had become limp or petrified, embodying the physical toll of work on the body. Awi’s cubicle may also critique the commodification of comfort; how even our rest (pillows, break rooms) is regulated and neutralized in the capitalist system.

I found Gilar’s cubicle delivered the internal psychological warfare of trying to “make it” in modern work culture. The cartoons resembled self-therapy scribbles, like the kind a worker might doodle between Zoom calls. They mocked motivational posters and highlighted the absurd pressure to succeed, masking personal collapse under performance metrics.

In Gilar’s habit of constantly offering us exhibition “mementos”, the metal tissue dispenser installation mocked corporate training, self-help culture, and the infantilization of young adults in the workforce.

The comic format implied ridiculous oversimplification, drew attention to how society expects people to transition smoothly into “adulting” with formulaic steps, something these guides parody. The inclusion of a guide on ‘how to poop’ intensified the satire; it leveled all human activity, from job interviews to biological needs, into “procedures” one must perform correctly. It was a brutal (and hilarious) comment on how hyper-rational systems rob life of nuance and humanity.

These whole depression cages were shadowed by a surveillance camera and Orwellian sign, “Big Brother is watching you,” a stark critique of surveillance culture. Awi’s gag added a layer of actual monitoring to the experience, reinforcing paranoia and loss of privacy.

In the tension of labor alienation, economic precarity, and identity dissolution, which they prompted, I noticed that the productivity in the presentation of issues that these installations provided could only end up at the primordial level, discarding the opportunity or productive potential as the gravity of critical debates surrounding the ethical sphere of Sabloy Station generation. In this light, I underline Eagleton’s perspective on what he expresses as a warning, where the naked form of postmodernism–such as this exhibition–supports the intense immersion of relativism and irony; critique becomes performative, and social action becomes paralyzed. The reality goes unchecked.

I could naively say that the grand “urgency” of the situations gradually devalued, (almost) bypassed by the playful surface-level fragmented analysis. There was a spirit of positivism which I carried. I was hoping to extract their clear attitudes as another constructive angle for action towards the whole jailhouse of realities and not only being “left out” to simply “enjoy” the suffering of the dehumanizing aspects of the modern work culture, covered in the dilemma and fussy romanticization of youth shocking disclosure.

From the milieu or the sensibility of Sabloy Station, one thing which I believe can be uplifted is their survival instinct among the depthless and pluralistic indecisiveness of social life. Their core was the fact that “they existed”.

Quoting Nauvaly, as the introduction text concluded, “— it’s already impressive if we don’t die.)”

Jasmine Haliza

Characterized by her slick, thoughtful articulation, Jasmine Haliza crafts art experiences into phrases to connect with readers via compelling chronicle. Jasmine Haliza explores ideas and narratives that reflect both critical curiosity and a commitment to meaningful communication. For her, writing is a form of independence and devotion to knowledge.

Titik Kumpul Forum

In(dies) Economy

Sabloy Station

Ason, Awi Nasution, Gilar, Kay, Tocka

Exhibition writer: Dhias Nauvaly

16 March — 15 April 2025

JNM Bloc

Jl. Prof. DR. Ki Amri Yahya No. 1

Yogyakarta 55253