What does it mean to call a space empty?

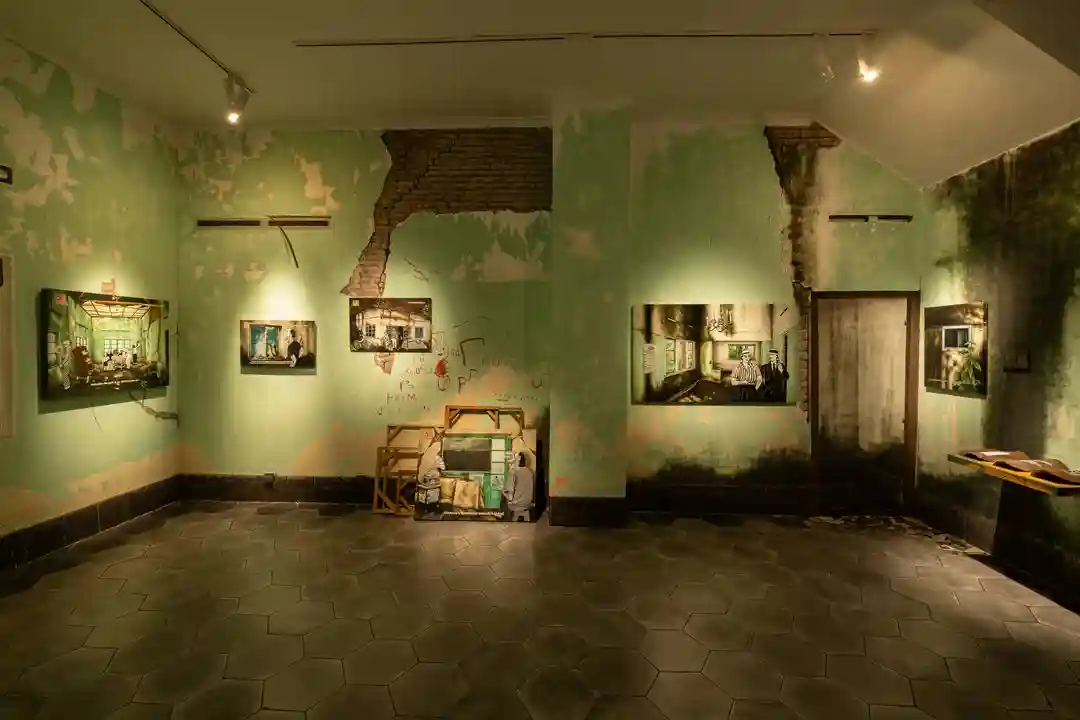

This question kept circling back to me as I moved through Suwung: Luruh dan Tumbuh (Suwung: Fading yet Pervading), Vendy Methodos’ solo presentation at kohesi Initiatives in Yogyakarta. Methodos builds his inquiry around the remnants of a former sugar factory and nearby houses in Sorogedug, on the city’s outskirts, where many of these buildings have been left in poor condition. The former sugar factory and the surrounding houses were once part of a colonial-era middle-class narrative that aspired for stability and prosperity. However, as industries changed, these homes lost their economic purpose and became trapped in limbo: not valuable enough (or perhaps too valuable) to renovate, yet not “entirely” abandoned. In this solo presentation, Methodos sees these spaces as if they carry traces of past lives, reimagining them through speculative gestures.

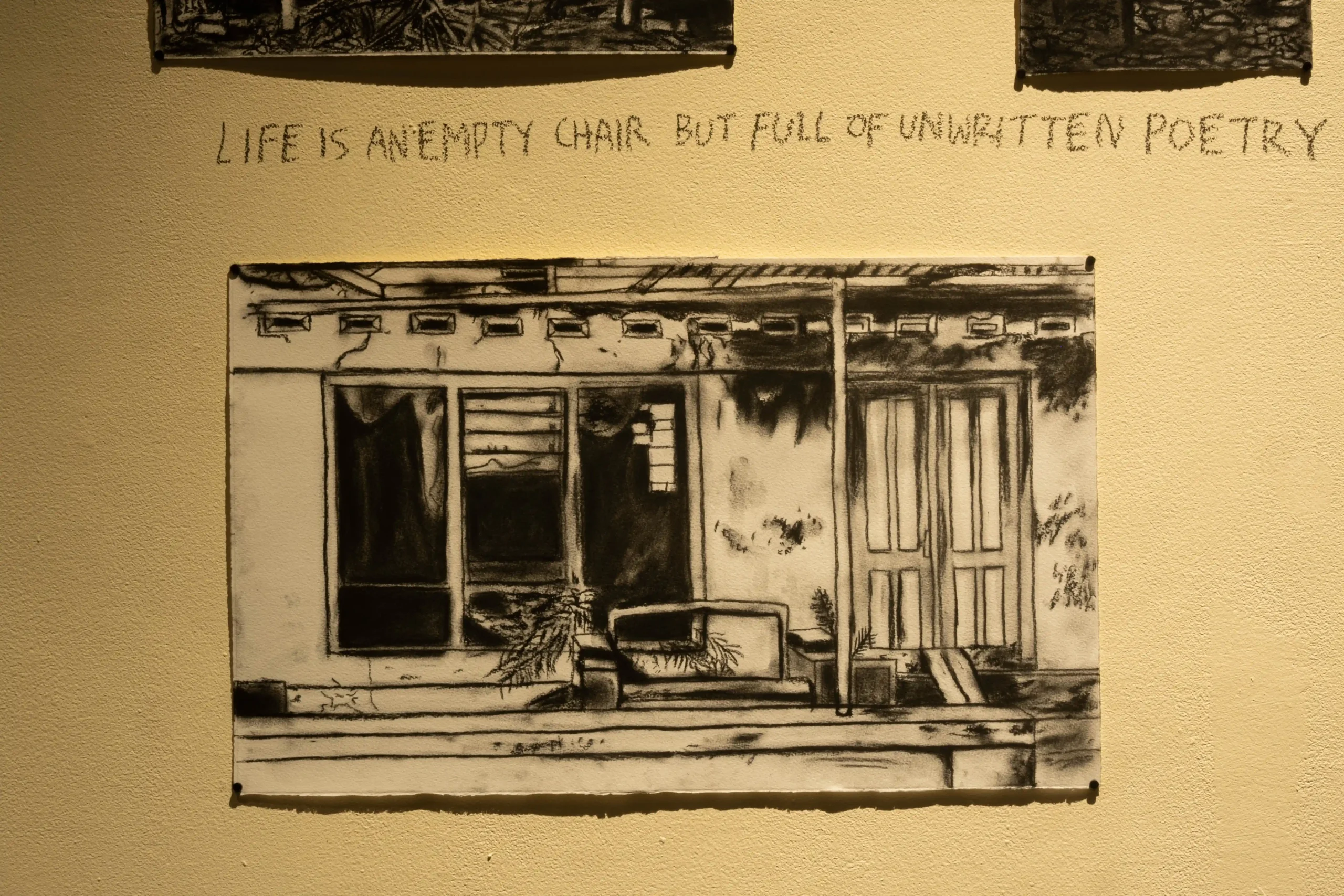

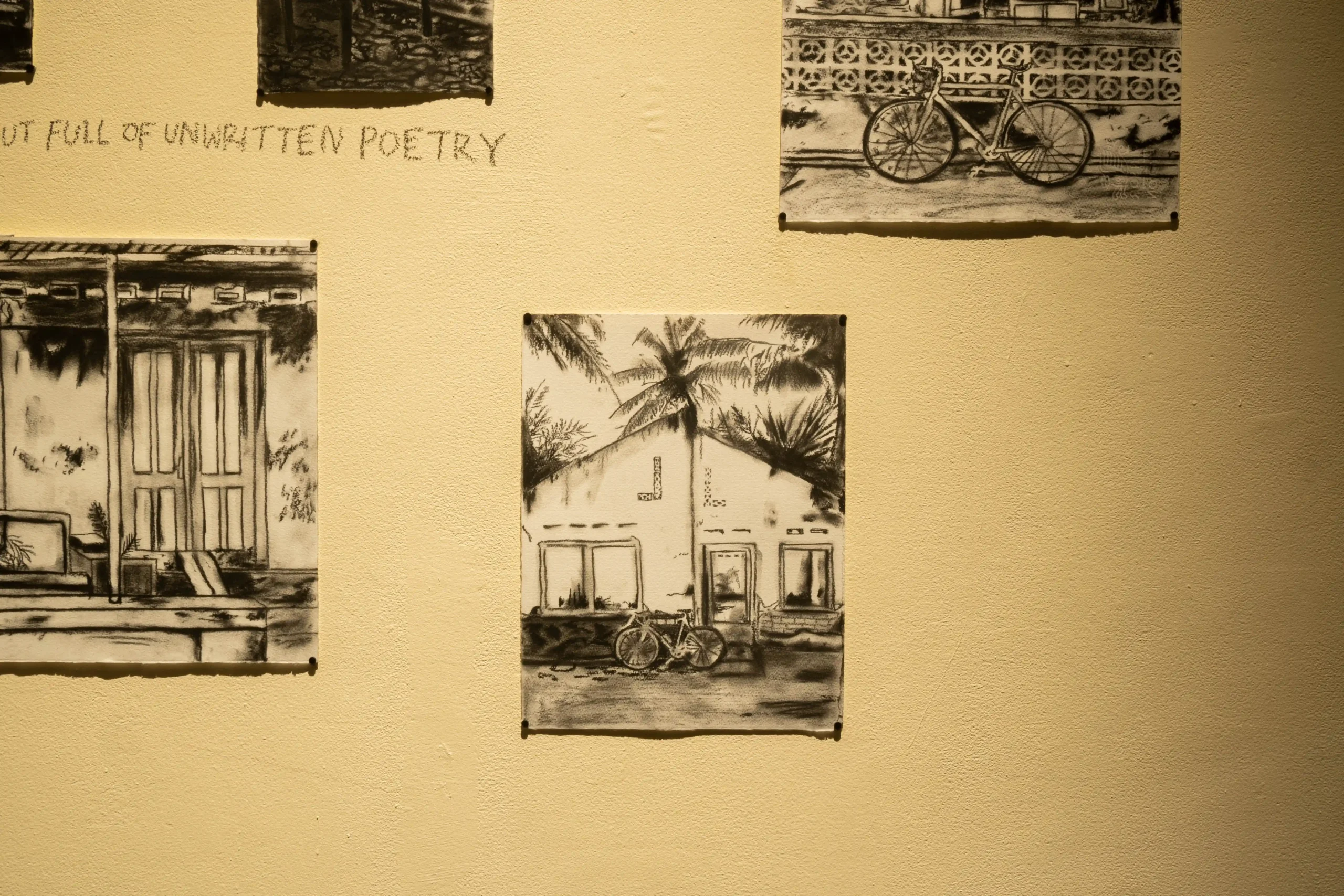

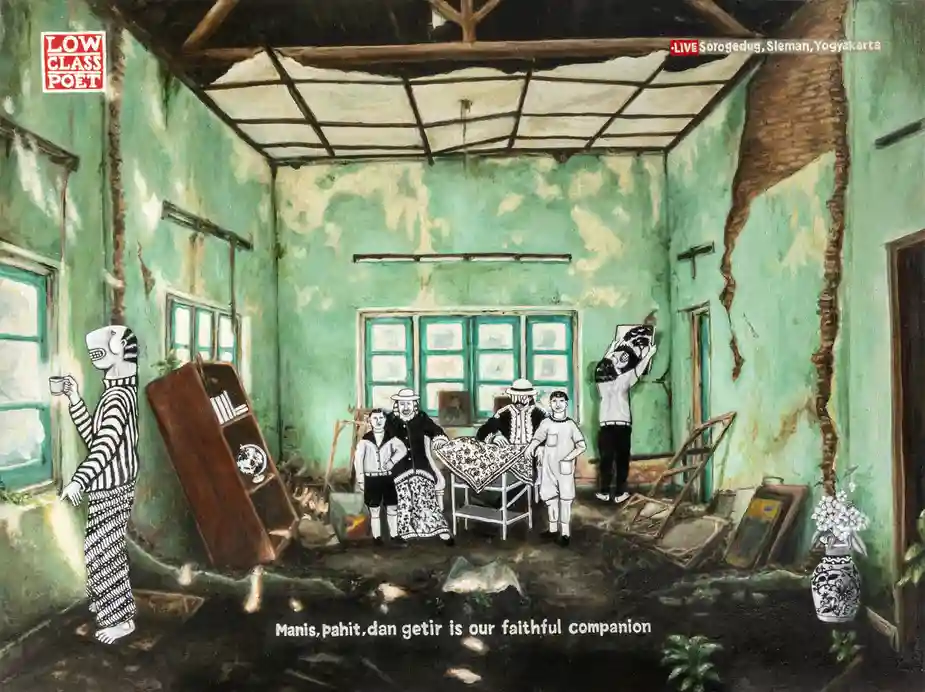

The idea of suwung, drawn from Javanese philosophy, frames the exhibition. As I reflected on this, it refers to a condition of openness, a kind of active emptiness that allows for presence. Methodos leans into this, conceptually, as his paintings layer realism with comical monochrome figures that inhabit the rooms. These figures emerge, in part, from Methodos’s research and conversations with those who still live near this area. It became clear to me that these figures are fictional beings that show how memory itself often tends to behave.

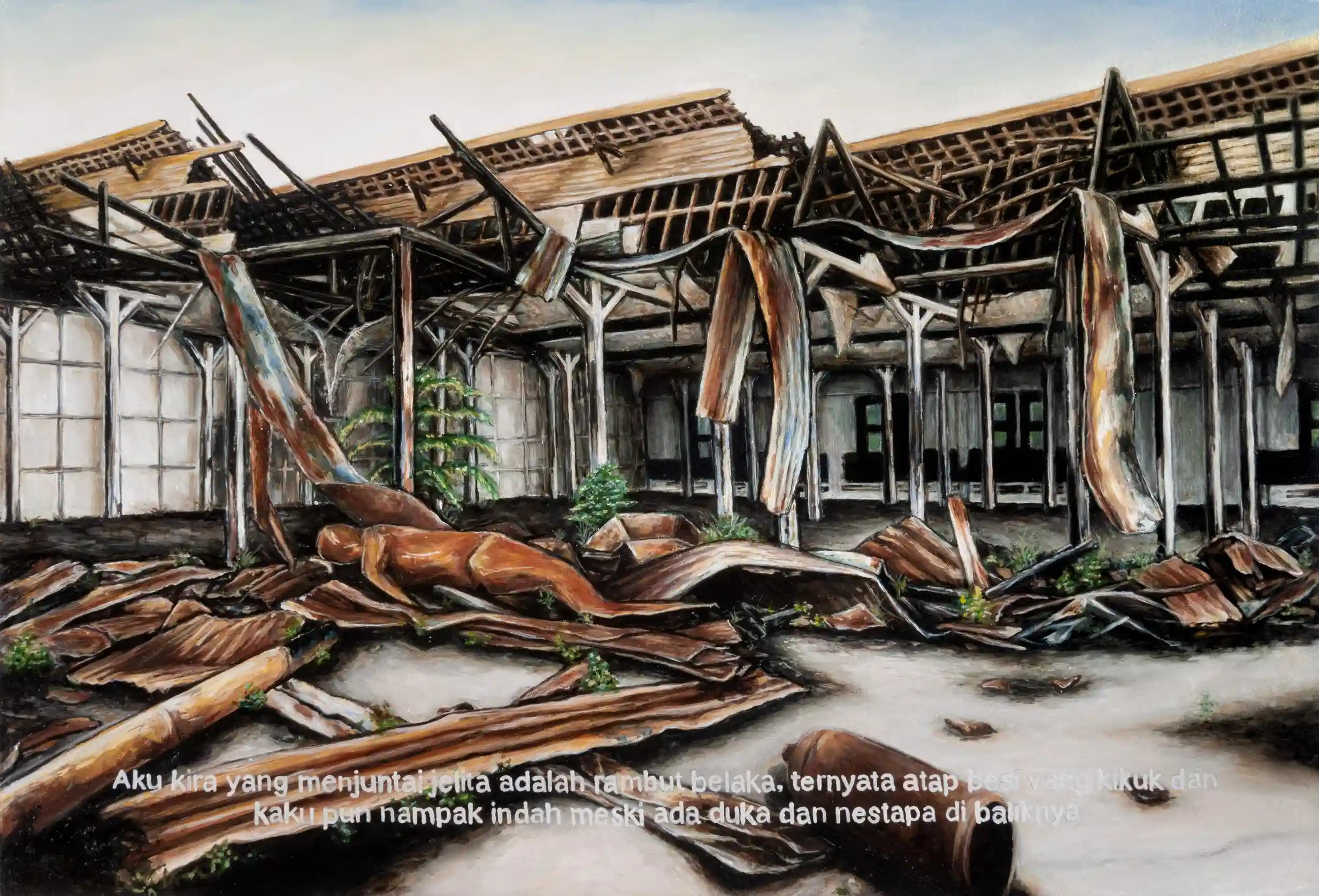

In one of the works, Manusia Adalah Makhluk yang Ulung dalam Memaknai Fenomena yang Sesuai Kehendaknya (Humans Are Creatures Who Are Excellent at Interpreting Phenomena According to Their Will, 2025) offered a view of the Sorogedug sugar factory long after its productive life had ended. The factory has a long history. Established and operating since 1874, it initially functioned as a sugar production site. In 1948, part of the complex was destroyed by Indonesian forces to prevent the Dutch military from using it as a base. By 1954, it resumed operations but was repurposed as a tobacco processing and storage facility for cigar production. By the late 1980s, the residential houses surrounding the factory were gradually abandoned, and in 2015, a massive fire devastated the remains of the old factory. And today, a few residents still live in the area.

Alongside the painting, a video installation records the space through light, wind, and the creaking architecture. There’s just the slow unfolding of a place that insists on being experienced rather than explained. Even in its near-collapse, the site seems to retain agency. As I watched, I thought about how difficult it is to convey such subtle forms of presence without overinterpreting them, and Methodos somehow manages to hold that scale. His work, in that moment, captured the idea that a place can remain “alive,” even when its physical form has begun to disintegrate.

Through this work, Methodos explores how “empty” spaces are perceived differently by different people. In this context, emptiness is shaped by changes in spatial function, which is a consequence of capitalism’s redefinition of ownership and property value. In Indonesia, abandoned houses are also often associated with myths and superstition, but beneath these narratives lies another social reality where these homes are left behind for a variety of reasons, often personal, sometimes unavoidable.

If emptiness (suwung) is Methodos’s point of departure, time is the condition through which that emptiness becomes perceptible. I found myself thinking about how time shapes our understanding of a space, how it gives meaning to what is left behind. So rather than establishing a singular thesis on the meaning of these homes, Methodos allows each work to operate within its own speculative logic, and in Tiga Periode dalam Satu Kanvas (Three Eras on One Canvas, 2024), I found myself pausing longer than expected.

In this work, he froze three different historical periods within a single frame. At the centre, a Dutch family formally poses for a portrait with their two children, representing the height of the Dutch East Indies, when the sugar industry was a pillar of the colonial economy. By the left window, elderly Javanese man (Ndoro Kakung) stands as if deep in thought. His coffee is almost finished, and the cigar he just smoked leaves a lingering bitterness. He seems to absorb life while observing the inevitable flow of time. Meanwhile, near the door, Kamerad Suroto, a character named by Methodos, struggles with his painting. He mutters to himself, frustrated with how art is increasingly losing its place in a society more interested in policing others’ sanity.

The figures do not seem to interact, but they inhabit the same room, each bearing a weight particular to their time, and Methodos places these components into one room as a metaphor for how the past, present, and future are continuously bound in ways we often fail to realise. It seemed clear that the house has recorded these lives, but not evenly, not with consent, and certainly not in a way we can easily understand.

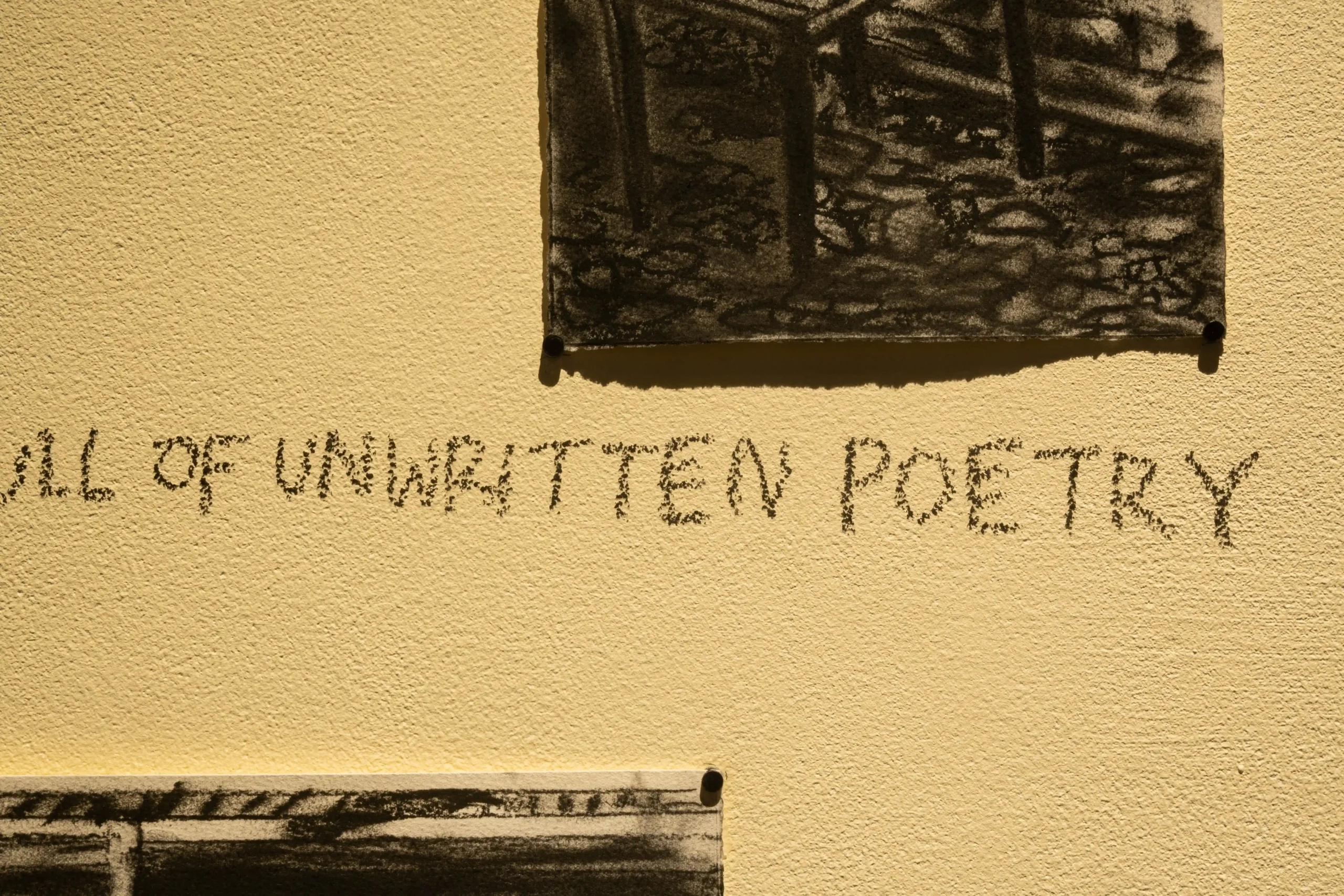

Looking back on the exhibition, nothing about it offers a definitive resolution, and Methodos leaves things open, refusing to narrate or to explain, especially in the face of spaces assumed to be empty. What emerges across these 16 works is a slow proposition that emptiness is never a stable category, and that space, much like memory, are conditions that flow through history, carrying with them traces of what was and what could have been.

Vendy Methodos is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice — rooted in Javanese social and cultural commentary — uses painting, murals, and sculptures to explore marginality, power, and everyday critique through satire.

kohesi Initiatives

Suwung: Luruh dan Tumbuh

by Vendy Methodos

curated by Alia Swastika

15 Mar— 4 May 2025

Tirtodipuran Link Building A

Jl. Tirtodipuran No. 50

Yogyakarta 55143, Indonesia